Hello Visitor! Log In

Peace: The Ultimate Condition and the Goal of Human Security

ARTICLE | August 1, 2023 | BY Pavel Luksha

Author(s)

Pavel Luksha

In the second decade of the 21st century, humanity again faces existential risks related to the risks of global wars. The collective decision to make wars obsolete (or not) will be the crucial choice that will determine our capacity to survive and thrive. Yet since the global security architecture has been established in the aftermath of World War 2, the notion of security and peace has greatly evolved. The proposal of the World Academy of Art and Science to evolve the concept of security as universal or human, should be connected to the reconceptualization of peace, which has to be seen as both the ultimate condition and the goal of human security policies. Based on the results of the Peaceful Futures project, three complementary types of peace—the absence of wars, the eradication of systemic violence, and the establishment of the collective state of harmonious being—are explored, and a comprehensive list of human security strategies is offered to attain these types of peace. The multidimensional approach to peace-making calls for multidimensional policies that can be structured along several action streams, including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological, and the roadmap produced by the project offers a pathway to create a peace-based civilization in the next 50 years. Moving to peaceful futures is a complex and multifaceted process that will require collective learning and coevolution of many social institutions and communities in the decades to come. Coupled with the efforts of human security, it becomes a feasible journey.

1. Introduction: We need to redefine our understanding of Security & Peace

When the Cold War ended and the Berlin Wall collapsed, hopes for the world flew high. Historians and futurists anticipated the new era when key international contradictions were resolved and humanity was on the pathway to a unified and borderless “flat world”, a “global village” that could provide enough for everyone to flourish.

Fast-forward three decades towards the beginning of 2023, humanity has not been able to come much closer to that optimistic vision than it did in 1990. The last three years saw the COVID pandemic, the disruption of global supply chains, trade wars, sanctions, secret agreements behind closed doors, the civic upheaval across the globe, unprecedented repressions with methods of surveillance state, and then the Russian invasion of Ukraine that keeps the world at the tip of toes due to the constant presence of a thermonuclear conflict risk. These political, economic, and social tensions have revealed how fragile the systems that maintain the wellbeing of humanity are—and how deeply interconnected the world is today.

"There is more to peace than the absence of wars."

During the first few months of Ukrainian war, the shortage of grain supply sent prices skyrocketing in Arab states, while the energy crisis toppled down the governments of Peru and Sri Lanka. The conflict between the US and China has disrupted the microchip sector and jeopardized the automotive and telecom businesses in Japan and Europe. Throughout the decades of stability and prosperity, it was easy to forget that the collective wellbeing, the technological progress, and the whole survival of global civilization are all contingent upon one fundamental condition—that peace prevails around the world. And today, global security systems appear incapable of maintaining that condition in the long run.

The main international body responsible for the preservation of global peace today is the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Formed in the aftermath of World War 2, UNSC aimed to overcome the shortcomings of the League of Nations and ensure international peace and security. It is not the point of this article to criticize the work of UNSC, nor to indicate its inability to fulfill its mission in all major wars of the last two decades, including the conflict in Kosovo, the invasion in Iraq and Afghanistan, and lately, the war in Ukraine. What I want to argue is that since 1945, the notion of security and peace has greatly evolved. The global security infrastructure that maintained the world order has outlived its mandate. But before rearranging it, we need to look at the basics and understand the conditions of peace and security in the 21st century.

From the perspective of the UNSC, security is primarily understood from the national standpoint, as the ability of states to protect and defend citizenry [Osisanya, 2018], while international security is the process of balancing out the interests of national security to ensure mutual survival and safety of nation states [Hafterndorn, 1991]. Clearly, this understanding prioritizes the role of nations as “agents of security” above any other social entities including businesses, NGOs, and social movements—which is fairly representative of the societal landscape of the 1940s but not the 2020s.

The definition of peace is even more interesting, as peace is defined as the period of absence of wars. Even though this ages-old concept of “negative peace” has been criticized, it continues to prevail as an operational definition. While many would intuitively agree with the definition, it clearly normalizes war as a way of being. But living through almost seventy decades of “long peace”, we also probably agree that there is more to peace than the absence of wars, and that conflicts, tensions, and violence can prevail in the society even when there is formally no war. Peace as the absence of wars is just the beginning of the path to create a truly peaceful society [Brzoska, 2021].

The proposal of the World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS) to evolve the concept of security as universal or human security, “a process that can and should be applied to enhance implementation of all socially-endorsed goals related to human rights and human development”, is highly commendable. It is time to move away from the limiting and nearly inadequate concept of national and international security in the hands of a handful of politicians, diplomats, and military officers. I argue in this article that we should connect this shift with the much-needed evolution of our understanding of peace. We should start seeing peace as both the ultimate condition and the goal of human security policies, as the integral measure of the success of human security efforts.

Throughout the second half of 2022, a group of international foresight and peace-building experts from over 40 countries in the world came together in a series of workshops to discuss the possibility of “peaceful futures”, future scenarios where global peace-based society is created within the next half a century*. The conclusion of the Peaceful Futures project is that this future reality is attainable, and that a clear pathway can be formed that brings peace-based civilization into existence.

Furthermore, the need to create such a new way of being is pressing. New military conflicts, engaging countries that own and develop weapons of mass destruction, elevate existential risks for humankind and the whole planet. With the development of new types of warfare—including autonomous military robotics, cyberwarfare, collective “mind hacking” through social media, various applications of the military AI, bio- and nano-warfare, and more,—wars of the future are potentially more devastating than anything we have seen until now. And risks of large-scale military conflicts will continue to grow year by year, driven by climate change, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation. It is expected that substantial areas will become unsuitable for agricultural production due to high temperature and lack of access to fresh water or will be flooded by rising oceans, affecting up to 1 billion people before 2050 [ETR, 2022].

Coupled with increased weapon lethality, future military conflicts can become a Russian roulette for the whole world—and such levels of risks cannot be further tolerated. Throughout the 21st century, humans will need to learn how to live without wars. To quote Buckminster Fuller, “either the war is obsolete, or humans are”. And the possibility of making wars obsolete is strictly contingent upon making human security and universal wellbeing the focal point of global, national, and local policies.

2. Why Peace is the Condition of “Everything”

Willy Brandt famously said: “Peace is not everything, but without peace everything is nothing.” As we time and again discover this simple truth, it is important to understand peace as the condition of “everything”.

First of all, it is important to recognize that peace, and not war, is a normal state of being throughout the existence of humankind. The Hobbesian “war of all against all” is an invented concept, and the reality of the “natural state” of prehistoric humans is very different from it. Homo sapiens appeared on our planet about 200,000 years ago, and even though there were sporadic violent conflicts between hunter-gatherer groups (similar to what happened from time to time among our primate ancestors [Morris, 2014]), more than often they peacefully coexisted with each other [Godesky, 2016]. War as a phenomenon only emerged about 10,000 years ago when human agricultural settlements first appeared [Ferguson, 2013]. And even then, civilizations of “long peace” prevailed in many regions of the world, where large human communities coexisted for centuries without engaging in any forms of military activities (the most famous examples are the civilization of the Indus River Valley and the first city-state of the Americas, Caral-Supe).

The recorded history of the last 2-3 thousand years is of course very different—it is abundant with wars (and that probably creates the impression that wars are an inevitable companion of humanity). Often, these wars were waged by large agricultural empires to acquire new lands and subdue or eliminate nomadic tribes that were seen as a source of instability. In the end, more powerful states expanded and established their order which brought peace and prosperity to their citizens. (Of course, there were very different causes and forms of war throughout the millennia, and many wars were also fought to destroy, pillage, and enslave.) Wars were also fought between rivaling states, demanding the evolution of social organization and military technologies—hence war has been seen as the engine of human development for a very long period in human history.

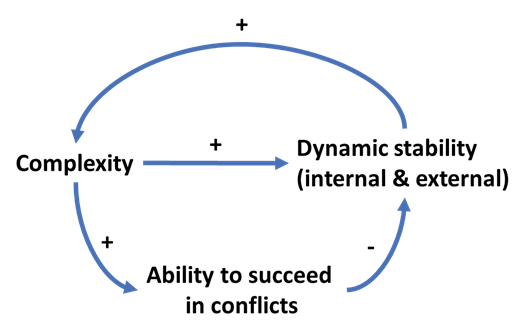

However, engaging in wars has always been a tricky business. Any complex social activity—from food production to architecture and creation of sophisticated technologies—demands social stability. Accumulation and evolution of knowledge is only possible in areas where human potential and material infrastructure are protected from destruction. States that learnt to maintain dynamic internal (and external) stability were the ones that could develop better, i.e., could increase their complexity. Their development would often encourage them to undertake risky military operations (or would provoke their neighbors to invade), therefore undermining stability. And so, the art of state governance was to find a healthy balance between states of war and peace, to determine when wars are desirable and when peace is preferred (Figure 1).

However, in the 20th century, and especially after two World Wars, humanity has learnt that the nature of military conflicts has changed. The lethality of weapons has grown exponentially through the 19th and 20th centuries, and any conflict between technologically advanced states would bring so much death and destruction that engaging in it would not yield any benefits that could justify the war for the population and elite (it could even bear existential risks for the nation, as was the case with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan). Since at least the middle of the 20th century, war has been primarily the business of “conflict entrepreneurs”, small elite groups that gain economic and political benefits during the stage of destabilization—and it does not bring benefits to larger societies such as nations [Coulomb, 2004].

Furthermore, all forms of complex human activities—research, financing, hi-tech manufacturing, or production of essential commodities such as food and energy—have transcended national borders a long time ago. Economies of the world became deeply intertwined, and any significant military conflict today disrupts the prosperity of the entire world, as the conflict in Ukraine clearly demonstrates. Global challenges, such as the climate crisis, require a greater level of cooperation that can only be achieved if we are able to maintain trust and inclusiveness at the global scale. To continue evolving, our civilization needs to evolve instruments and institutions that maintain its internal and external dynamic stability. We need to identify various forms of stability disruptors that go way beyond military conflicts—and to find new strategies for addressing them.

One of these important disruptors today is the unhealthy relationship between the human population and the planet. For centuries, more-than-human nature has been seen as a resource for humans to exploit—the land, the forest, wild animals and fish were all available in abundance. Humans have forgotten the fundamental truth: human societies are a part of and are contingent upon natural systems of Earth. Destabilizing natural systems will inevitably destabilize our society, and the only way to guarantee our own survival and evolution is to learn to restabilize them. For too long, humans waged war on natural systems of our planet, and this destabilization has shown itself today in the form of climate change, soil degradation, and loss of key species such as pollinating insects. It is time to make peace with nature again.

Maintenance of rights and conditions of human individuals and communities, as well as peaceful coexistence with local and planetary natural systems, is therefore the only way to ensure the survival and thriving of our species. Our notion of peace needs to be expanded to reflect this fundamental recognition.

3. Peace is a Multidimensional Phenomenon

Let us explore the dimensions of peace as a condition of complex human activity—the dynamic external and internal stability of human societies that ensures that complex activities can happen. The first definition of peace already mentioned above is “the absence of wars”. However, wars are only one form of violent conflict. Organized systemic violence can take many forms, and it often either becomes “a war in disguise” of its own (for example, when an oppressed ethnic group is destroyed through prison camps and tortures), or a root cause that instigates wars. Therefore, peace can also be defined as “the eradication of systemic or structural violence”. Finally, we know that when peace is achieved, the wars are stopped and the violence is eradicated, the society enters a particular state of (collective) being and consciousness free from disturbance, a state of calmness, tranquility, and harmony—which we can call a “positive” definition of peace.

These three definitions—absence of wars, eradication of violence, and state of tranquility—are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they highlight distinct aspects of what peace is, or different “types” of peace. Societies that adopt a particular understanding of peace would also have different objectives of achieving and maintaining it (Table 1).

Table 1: Types of Peace

|

# |

Type of Peace |

Objective of Achieving & Maintaining Peace |

|

1 |

Absence of wars |

Society prioritizing non-destructive methods of conflict resolution |

|

2 |

Eradication of systemic violence |

Society embracing values of collaboration, care, and love |

|

3 |

State of tranquil / harmonious being |

Society existing in harmony and thriving for all humans & non-human entities (intra & inter-personal as well as intergenerational) |

We can clearly see that these types of peace are interconnected. On the one hand, “peace 1” is a necessary condition to achieve “peace 2” (we cannot eradicate systemic violence if wars continue), and “peace 2” is a condition to achieve “peace 3” (societies cannot be tranquil and harmonious if they continue various forms of systemic violence). At the same time, cultivation of “peace 3” (tranquil being) strengthens the possibility of achieving “peace 2” (eradicated violence), while eradication of violence (“peace 2”) also removes the root causes of wars (“peace 1”).

Another good way to understand tree types of peace is through the lens of “three horizons” model offered by Bill Sharpe [2013]. This model suggests that innovations, institutional frameworks, and conceptual perspectives are spread across Three Horizons—horizon 1 being the dominant yet the most problematic “way of being” (i.e. its contradictions have already been revealed), horizon 3 is a long-term sustainable “way of being” (resolves problems of horizon 1) that will dominate our future but is only in the nascent state today, and horizon 2 is a “bridging” “way of being” that addresses some of the challenges of horizon 1 and can help us transit to horizon 3. From this perspective, “peace 1” is evidently the dominant perspective today, while “peace 3” is still perceived as a utopian future state of being. “Peace 2”, eradication of systemic violence, is a bridging way of addressing peace-making challenges.

In our recent work with the Peaceful Futures project, we used these three notions of peace both to understand the variety of forms of disturbance to peace, and also to map out various strategies for overcoming these disturbances (Table 2). The list is sufficiently comprehensive but not complete—other important causes of disruption and methods of overcoming them can also be included.

Table 2: Causes of Disruption of Various Forms of Peace and

Methods to Eliminate or Overcome Them

|

Type of Peace |

(Some) Causes of Disruption |

(Some) Methods of Overcoming or Eliminating the Cause of Disruption |

|

Peace 1: Absence of Wars |

Autocratic & Nationalistic Ambitions |

Democratization / bottom-up governance, government transparency, engaging younger generations in decision making Making offensive war internationally illegal |

|

War Oriented Patriotism |

Deromanticizing wars and redefining patriotism through peaceful / constructive alternatives |

|

|

Interests of Military Industrial Complex (MIC) & Its Owners |

Reduction in military spending, |

|

|

Warmongering: Intentional Manipulations of Public Opinion |

Critical thinking, increased public control over media & social platforms |

|

|

Peace 2: Eradication of Systemic Violence |

Lack of Basic Human Security (Food, Energy, Shelter, Healthcare) |

Redefinition of human rights to include peace-inducing conditions, guaranteed provision of basic services, Universal Basic Income (UBI) |

|

Economic & Political Inequality |

Increased corporate and public financial transparency, progressive taxation, UBI |

|

|

Monopolization |

Antitrust practices, change of IP legislation |

|

|

Unfair Supply Chains |

Transparency and accountability of supply chains |

|

|

Domestic / Family Violence |

Zero domestic violence tolerance policies, non-violent communication practices, family & community therapy |

|

|

Ecocide: Violence Towards Natural Ecosystems |

Promotion of regenerative economic models, legal systems supporting rights of non-human entities |

|

|

Peace 3: |

Habits & Behavioral Patterns that Reproduce Systemic Violence |

Culture of inclusivity, nonviolent communication Socio-technical systems (e.g., AI) “nudging” people to choose nonviolent behaviors |

|

Personal & Collective Traumas |

Various forms of healing including ones done through traditional & indigenous ways of healing |

|

|

Egoism & Existential Poverty Disconnection from other Humans & Nature |

Empathy-focused education, education focused on cultivating planetary consciousness, cultivation of Inner Development Goals |

|

|

Lack of Hope & Inspiration |

Education & art focused on imagination and envisioning of desirable futures |

Addressing disruptions to “peace 1” primarily requires changes in the governance system that reduce the possibility of deciding to enter a war. Disruptions to “peace 2” are multi-dimensional—and these are perhaps the closest to the idea of human security as promoted by WAAS, “enhancing implementation of human rights”. Disruptions to “peace 3” are primarily cultural and spiritual, and therefore require more subtle forms of counteraction through education, art, and spiritual practices.

4. Journey to Peaceful Futures

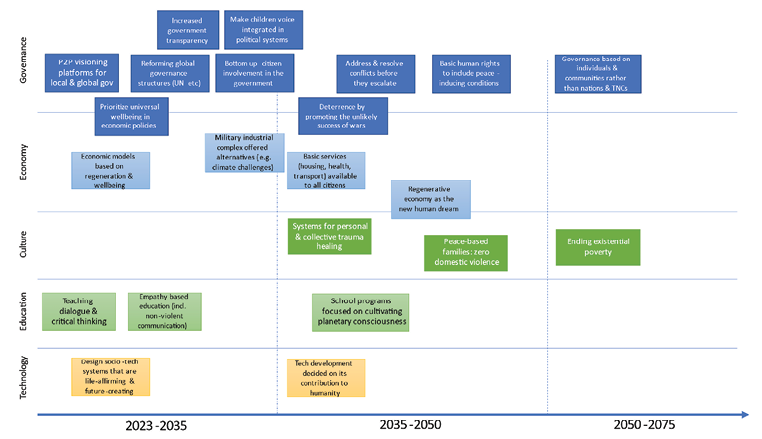

The multidimensional approach to peace-making calls for multidimensional policies. However, not all efforts can bring comparable results, and some of them can act as “enablers” of others. In other words, if some projects are accomplished, they create conditions and raise the probability of success of other projects. The Peaceful Futures project has identified over 60 initiatives to cultivate global peace, and the team has been able to prioritize them through the Structured Democratic Dialogue process (also used in the setting of conflict resolution and complex policy making [Laouris, Michaelides, 2017]). This work has identified 22 key initiatives that establish the “critical path” towards the peaceful futures scenario in the next 50 years (Figure 2).

The biggest group of initiatives relates to democratization processes, such as the increased government transparency, participatory design of national priorities, and the integration of children and youth’s voices in the political system. Second group of initiatives promotes a new model of economy that is fair, just, and regeneration-focused—including the provision of basic services to all citizens and prioritizing universal well-being (instead of purely economic indicators such as GDP) in economic policies. Another large group of initiatives is about enhancing peace-oriented cultural values and practices through empathy education, promotion of planetary consciousness, healing personal and collective traumas, and nullifying domestic violence.

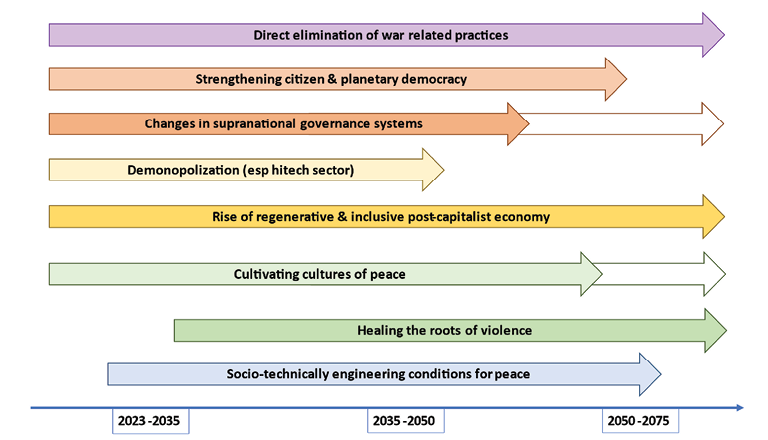

When a larger set of 60+ initiatives is taken into account, it can be clustered into eight “action streams” that spread over the next 50 years (Figure 3). Let me briefly describe each of these streams:

- Political initiatives relate to strengthening the citizen and planetary democracy, and also the transformation of the supranational governance system (including the provision of legal rights to the entities of more than just human nature);

- Economic initiatives involve demonopolization and “rehumanization” of supply chains (which could be one the largest sources of structural violence and inequality), and also the promotion of the regenerative and inclusive economic models and principles;

- Socio-cultural initiatives include cultivation of peace-oriented values and behaviors through education, art, and media, and also healing of the roots of violence through trauma-oriented work and spiritual practices;

- Technological initiatives tap into the potential of socio-technical systems to induce collective behaviors, so that these systems can be designed to be life-affirming, and future- and opportunity-creating to all stakeholders, and some of these systems can be used to “nudge” people to act more peacefully or help them make decisions that minimize the potential of conflicts;

- Finally, direct elimination of war-related practices is a political reorganization and cultural redesign that makes wars unwanted and non-feasible.

[Preliminary Project Results]

A number of peace initiatives such as the Positive Peace Report [2022] suggest that we need to shift from negative to positive conditions for peace and flourishing of our civilization by defining the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies. “Peaceful Futures” offers a comprehensive roadmap that bridges the current social reality—unstable, fragile, and vulnerable—with the possible future where wars could be done away with once and for all. This roadmap is of course a hypothesis, and its feasibility needs to be further scrutinized to make it a reality. What it highlights is that global peace cannot be achieved unless the systemic transformation of social institutions, political and economic priorities, and cultural patterns occurs on a global scale. Unlike earlier studies on the subject, it also emphasizes the need of socio-economic transformation towards the regenerative paradigm, as well as the essential role of individual and collective healing processes to create a peaceful society. Most importantly, peace requires the redesign of economies, societies and technologies on the new human- and planet-centered principles so that human needs and rights are met, and human development is enabled. This is very aligned with the call made by WAAS to reorganize the global security system.

5. Conclusion: Peace as the Focal Goal of Human Security Efforts

As we can see from the above discussion, peace is the condition to “everything” (any complex human activity, whether economic, social, or cultural), and it can only be achieved as part of the transformation of human civilization. The Millennium Development Goals, and later the Sustainable Development Goals 2030, are a beautiful effort to operationalize the directions of such transformation. We need to continue defining additional areas and priorities for global governance in the 21st century.

"Peace can only come from within, and it needs to be raised bottom-up through shifts in consciousness, behavior, and culture."

The notion of human security, as well as the redefined notion of peace (from the perspective of three definitions provided in this article) can set some of the critical parameters for the next 50 years to come. The next half a century can easily be the most definitive in the history of humankind, when we will either “make it or break it” as a civilization and as a species. Many, like astronomer Martin Rees and late biologist James Lovelock, are highly skeptical of the human collective ability to live beyond the 21st century, giving up to 50% chance to “break it” scenario. Risks of global wars, environmental catastrophes and societal collapses are growing, but so does our potential to mitigate them. We are indeed “in the midst of an evolutionary crisis”, as Margaret Mead [1964] indicated over half a century ago. The collective decision to make wars obsolete (or not) will be the crucial choice that will determine our capacity to survive and thrive, and achieve human security for all.

Moving to peaceful futures will not be a linear process with a simple straightforward “solution”. It is a complex and multifaceted process that will require collective learning and coevolution of many social institutions and communities over the decades to come. Peace cannot be engineered for the general public by national and global elites, it cannot come “top-down” from power structures, and no reorganization of the UN Security Council will be sufficient to make it prevail. Rather, peace is “everybody’s business” that will require the engagement and commitment from every member of society. Peace can only come from within, and it needs to be raised bottom-up through shifts in consciousness, behavior, and culture—even though power structures will also play an important role in enabling it and making it stay.

But the first and the most important condition of making wars obsolete is that we admit the possibility of a peace-based civilization in our minds. Then we will be able to see, in the words of Martin Luther King [1964], that “peace represents a sweeter music, a cosmic melody that is far superior to the discords of war”, and by changing our economic and cultural priorities we are able to “shift the arms race into a ‘peace race’”. Is this not the magnificent goal of human security efforts?

References

- Brzoska M. (2021) Is Peace the Absence of War? Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy Blog post 09/22/2021. Link: https://ifsh.de/en/news-detail/is-peace-the-absence-of-war

- Coulomb, F. (2004) Economic Theories of Peace and War. London: Routledge.

- ETR (2022) Ecological Threat Report: Analysing Ecological Threats, Resilience and Peace. Institute for Economics & Peace. Link: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/ETR-2022-Web-V1.pdf

- Ferguson, B. (2013) “The Prehistory of War and Peace in Europe and the Near East”. In D. Fry (ed.) War, Peace, and Human Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Godesky J. (2016) Hunter-gatherers live in relative peace. Link: https://www.rewild.com/in-depth/peace.html

- Haftendorn, H. (1991) “The Security Puzzle: Theory-Building and Discipline-Building in International Security”. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 3-17

- King, M.L. (1964) Peace Nobel Prize Lecture. Link: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/lecture/

- Laouris Y., Michaelides M. (2017) “Structured Democratic Dialogue: An application of a mathematical problem structuring method to facilitate reforms with local authorities in Cyprus”. European Journal of Operational Research, No.1, pp. 1-14

- Mead M. (1964) Continuities in Cultural Evolution. Routledge

- Morris, I. (2014). War! What Is It Good For?: The Role of Conflict and the Progress of Civilisation from Primates to Robots. MacMillan

- Osisanya, S. (2018) National Security vs Global Security. Link: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/national-security-versus-global-security

- PPR (2022) Positive Peace Report. Analysing the factors that build, predict and sustain peace. Institute for Economics & Peace. Link: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/positive-peace-report-2022-analysing-the-factors-that-build-predict-and-sustain-peace

- Sharpe B. (2013) Three Horizons: The Patterning of Hope. Triarchy Press

* I would like to indicate that Peaceful Futures project is the result of work of teams from six organizations that came together as project partners: Global Education Futures, VZOR Lab, School of International Futures, Next Generation Foresight Practitioners, and later, Future Worlds Center and Ecocivilization. While many findings expressed in this paper represent results of the collective work (and therefore should be attributed to the whole team), the main conclusions are ideas are expressed are my own, and I take responsibility for interpretations and statements in this article.