Hello Visitor! Log In

Power and Climate Change Governance: Negative Power Externality and the Brazilian Commitment to the Paris Agreement

ARTICLE | May 11, 2019 | BY Danielle Sandi Pinheiro

Author(s)

Danielle Sandi Pinheiro

Abstract

Brazil is facing a climate change governance puzzle in which we can identify economic and political instabilities interacting in a conflicting manner with power relations. The exercise of institutionalized power through the national government and international institutions should be enough to reach an environmental second best outcome—the institutional power coordination of the environmental agenda. However, domestic governance and institutionalized power relations are working in a contradictory manner, since the second best solution is not enough to reach an effective agenda for climate change and sustainable development. We call this situation as a negative power externality. This could be a signal that the strictly economic view of the free market system is not sufficient to handle the environmental concerns and sustainable development policies.

1. Introduction

Although the attention paid to climate change by the government and civil society has been growing in Brazil over the last few decades, effective public policies are quite unstable. The short run economic and political agendas prevail over an integrated governance agenda for climate change and sustainable development. The gap between official speech and effective actions for climate change denotes an interplay among the uncertainties about the long run climate change impacts over the country, the abundance of natural resources, and the multiple policy cycles following political and economic circumstances.

For instance, before the impacts on climate materialize, the process of decision making has been filled with controversies and political conflicts about the sources of power that emerge from groups of interest and priorities that arise from the political-economic business cycles. In this sense, some authors have referred to climate change as a “wicked problem par excellence”, since it is hard to implement policies for governance adaptation and there are vested interests involved. (Rittel & Webber, 1973), (Lazarus, 2008), (Davoudi et al, 2009), (Jordan et al, 2010). Besides this, different levels of social power relations emerge from this scenario.

As Vink et al (2013) point out, the government’s adaptation to climate change might be characterized by inherent uncertainties, given the long term character of this policy issue, the involvement of many interdependent actors with their own ambitions, preferences, responsibilities, problem framings and resources and the lack of a well-organized policy domain for enhancing and monitoring climate adaptation in the policy agenda. Following this view, though Brazil has ratified the Paris Agreement, we found evidence that the Brazilian society has been facing a climate change governance puzzle in which we can identify connections among economic and political problems and power relations. These problems are often interconnected with the three levels of social power: social potential power, institutionalized power and informal power.

These different forms of power are interconvertible and interact with other levels and types of social power, and the controversial actions the country has been taking concerning the climate change agenda is a result of negative power externality. In this sense, a negative power externality is a situation where the government and the society are conscientious about the challenges and risks of exploiting natural resources, but because there is flexibility and interchangeability between power relations jointly between the political-economic business cycles and governance agendas, the best choices in terms of climate and sustainable development policies are not made as expected and the environment is harmed.

This article suggests this concept as an idea of how to look for a more integrated approach in the environmental policy that deals with the interconnections among social power relations, economics and governance matters. This concept is called ‘power externality’. After this introduction, this article proposes in Section 2 a theoretical way to integrate governance elements that have been applied to climate change negotiations in order to propose an analytical path relating them to economic welfare theory and social power relations. In Section 3, a brief case study is discussed considering the negative power externality situation Brazil is facing on its climate change agenda. In Section 4 we summarize the analytical potentials and limitations of this proposition and point out further research directions.

2. Climate Change Governance and Economic Efficiency

Sustainable climate policies are the most complex and arduous actions to be implemented by countries. The central problem is to motivate the society and governments to articulate individual and collective actions in order to do more than they would do under ordinary political and economic business scenarios. There are two traditional governance approaches to handle this: the top-down approach and the bottom-up approach. The top-down approach settles assurance problems through legally binding obligations. On the other hand, the bottom-up approach has confidence in transparent and voluntary commitments that are subject to regular reviews. A mixed approach is possible too. Following this method, countries accept a bottom-up structure in terms of framework conventions and then adopt top-down protocols within a convention that binds them to accomplish obligations.

In a strictly economic view, these governance approaches could be seen as a way to deal with the contentions between the global society’s needs in terms of consumption and production and the scarcity of natural resources. A world of free market relations and spontaneous environmental and climate consensus, in terms of political thought and sustainable use of natural resources, can be seen as the first best outcome, as can be seen in the analogy of the Pareto efficiency criterion in the welfare theory in economics. The earliest works that support the efficiency criterion argument can be found in Pareto (1906) and Lancaster and Lipsey (1956). However, this scenario is not achievable. Therefore, the governance challenge faced by governments and civil society focuses on how to deal with the governance approaches, since countries across the world have different levels of development and socio-economic needs that frequently put in check the achievement of a climate change consensus.

For instance, the second best situation is more likely to be reached in the real world. Governance structures play a crucial role, in terms of the second best climate and environmental policies, since the first best option is never achievable. This means that the ideal or the first best solution of a full environmental consensus in terms of sustainable use of natural resources that would generate global efficiency is not feasible. In this situation, it is not clear if only one or a few environmentally committed countries will be able to increase the efficiency of climate policies as a whole. Thus, the countries may often have to negotiate in terms of governance structures that are more achievable, as we mentioned before.

The outcome of countries’ negotiations is the second best solution and we consider that it denotes a result of exercising institutional power. Institutional power as a way of reaching the second best solution indicates an exercise of power through the authority of formal social systems and institutions—the national governments and international organizations like the United Nations and its leadership in the climate change negotiations.

2.1. Power Externalities

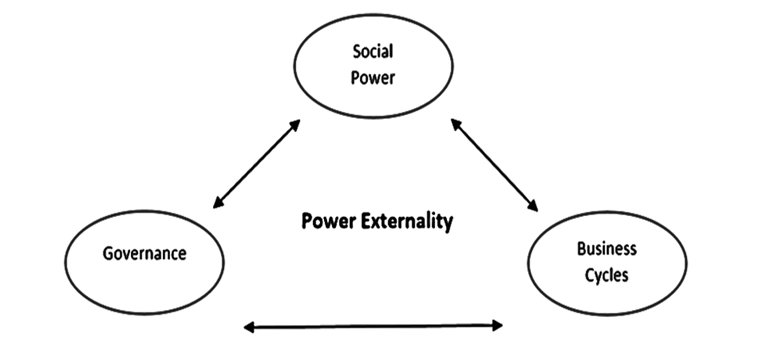

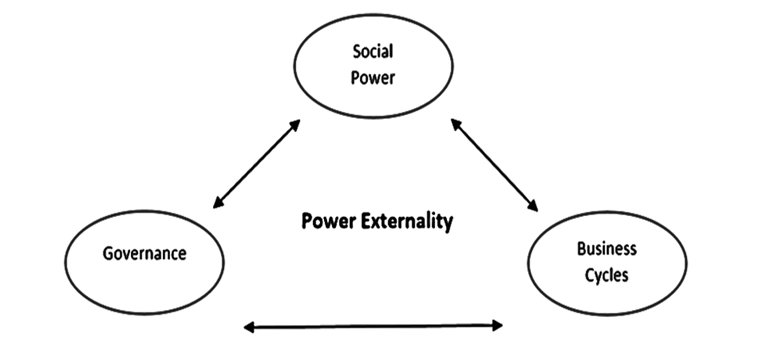

When we analyze the governance approaches involving the environmental and the climate change agendas in terms of welfare economic theory and social power relations, another interconnection that could emerge is what we will describe as power externalities. In this sense, we can define power externality as a situation where the interconnected social power relations jointly with the political-economic business cycles and governance agendas affect a third part, in this case the environment, not directly related to this matter. Schematically, we can structure this argument as shown in Figure 1.

“Our conception of power externality considers the interconnections between economics and the entire system of social power relations and governance structures.”

Our argument is that since the economic decisions of production and consumption are interconnected with political and business cycles, power relations are the arena that governs these relations. In this sense, the power externality concept we are proposing is used in the same vein as in contemporary economic theory, but with a difference. Our conception of power externality considers the interconnections between economics and the entire system of social power relations and governance structures.

Power relations are very useful for economic and environmental discussions since they bring out principles about the reality of the social power relations: “a rational assessment of the present political, economic, social system needs to be founded on an understanding of the underlying reservoir of social potential, how it is converted into effective power, how power is distributed and how the special interests skew its distribution and usurp the power for private gain.” (Jacobs, 2016). This wave of thinking that emphasizes theories concerning human-centered development can also be seen in Nagan (2016).

Following this view, when society produces and consumes goods and services, beyond the demand and supply of socio-economic agents, there is a third part, external to this human mechanism that is affected in many ways. This part is the environment which faces the resulting effects of global warming and climate change. To handle the economic and political dilemmas that emerge from these connections, governance structures deal with the contentions that could arise from them.

We can have a negative and a positive power externality as we do in current economic theory. In this sense, a negative power externality is a situation where the government and the society are conscientious about the challenges and risks of exploiting natural resources, but because there is flexibility and interchangeability between power relations (jointly between the political-economic business cycles and governance agendas), the best choices in terms of climate and sustainable development policies are not made as expected and the environment is harmed.

On the other hand, a positive power externality is a situation where the government and the society are conscientious about the challenges and risks of exploiting natural resources, there is flexibility and interchangeability between power relations (jointly between the political-economic business cycles and governance agendas), and the best choices in terms of climate and sustainable development policies are more likely to be achieved and the environment is benefited. A positive power externality is a good outcome for the environment and the society as a whole since it leads to improvements in general.

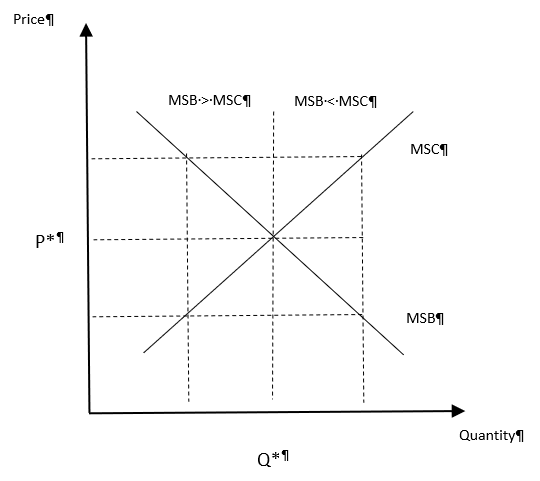

In order to demonstrate this argument, we can use an analogy concerning the allocative market efficiency traditional approach in economics. We will define allocative efficiency in terms of two concepts: Marginal Social Cost (MSC) and Marginal Social Benefit (MSB). In this case, we will propose a definition connected with the power externality approach we are suggesting.

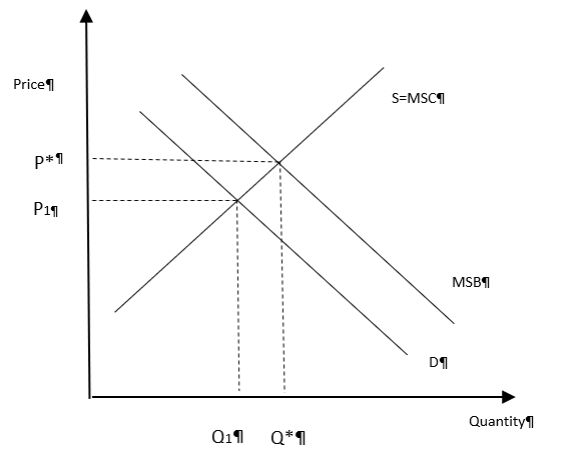

In this sense, MSC equals the extra cost to society of producing one more unit of output using natural resources. The law of diminishing returns implies that MSC will be sloping upward. MSB equals the extra benefit to society of consumption of one more unit of output using natural resources. The law of diminishing marginal utility implies that MSB will be sloping downward. This analysis is shown in Figure 2.

As long as MSB exceeds MSC, society is better off due to increasing output. In the opposite way, society is better off due to decreasing output as long as MSB is less than MSC. The allocative efficiency occurs where MSB is equal to MSC. In the market economy, the demand curve measures the maximum price (P) that consumers are willing to pay for a given quantity of a good. In this way, the demand curve (D) is a measure of marginal benefit for all consumers in the market. In the absence of externalities, the market demand measures the MSB. Then, we can say that MSB = D = P. For the supply side of the economy, in perfect competitive markets, the supply side (S) is a measure of the marginal cost (MC). Consequently, in the absence of externalities, the marginal cost equals the marginal social cost. Similarly, we can say that MSC = S = MC.

In this sense, allocative market efficiency occurs whenever MSB = MSC. When a third part is harmed, we call this a negative externality. In terms of the allocative efficiency argument, MSC (which includes the cost to the third part) does not equal the supply curve. So, MSC exceeds the supply curve. On the other hand, when a third part is benefited, we call this a positive externality. It occurs when the MSB (which includes the benefit to the third part) does not equal the demand curve. Hence, the MSB exceeds the demand curve. Despite the traditional graph approach we are presenting, a more formal development in welfare theory of externalities can be seen in Lin & Whitcomb (1976). We can also find a modern approach in Berta (2017).

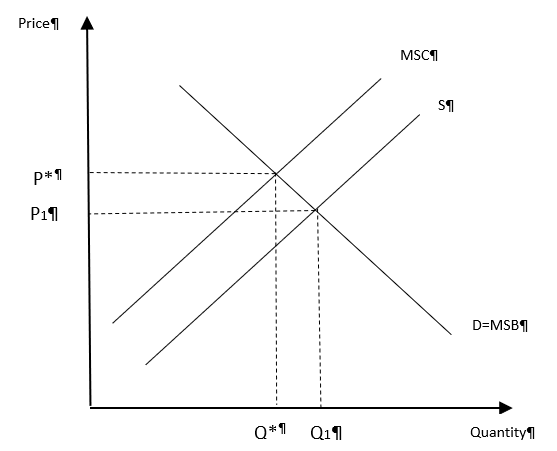

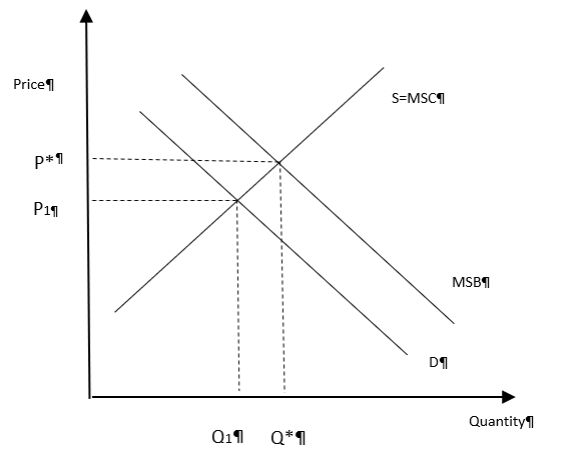

Negative and positive externalities, strictly in the traditional economic sense, are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. These examples deal with the approaches of making furniture by cutting down rainforests (Figure 3) and consumption of clean energy, like eolic energy (Figure 4).

In both graphs, the market equilibrium provides resource allocation where demand (D curve) equals supply (S curve), which occurs in both graphs at point P1Q1. Therefore, the market price is given by P1 and market quantity of resources allocated is represented by Q1. However, allocative efficiency occurs where the MSB curve equals the MSC curve, that is, at point P*Q*. As a result, when there are externalities in perfect free markets, resources will be misallocated and the market will be inefficient. This means that an idealistic world consensus on sustainable use of natural resources is not achievable.

When there is a negative externality, the market equilibrium will produce too much output at a low price. In environmental terms, this means that the exploitation of natural resources is excessive and undervalued. In the case of positive power externalities, the market will produce too little at a low price. This means low productivity and undervaluation of production.

As demonstrated before, both types of externalities end in allocative inefficiency. This allocative inefficiency could be interpreted the following way: due to flexibility and interchangeability between power relations and political-economic governance agendas, the first best solution, in terms of free competitive markets, or the first best choices, in terms of spontaneous and consensual climate and environmental development policies, are not made as expected. In this sense, climate policies are a result of institutional power relations and the second best environmental solution. In this context, the second best solution gives us a way to overcome power externalities through institutional power intervention jointly with an appropriate governance scheme. For instance, national and international organizations, as well as government institutions in all levels, can do it.

“The principle of economic externalities partially considers the effect of human exchanges over an agent external to this mechanism because it sees only the market logic, without considering the integrality of all elements involved in economic activity.”

2.2. Overcoming Power Externalities

A way to overcome power externalities is to apply appropriate public policies in the exercise of institutionalized power by governments (or international organizations), since the economic agents do not consider the entire effects of their activities over nature or the society as a whole. As Pigou (1920) noted in his book The Economics of Welfare, “private business pursued their own marginal private interests. Industrialists were not concerned with external costs to others in society” (or in the environment), since they have no incentives to internalize the full social costs of their actions. This is an early exposition of the externality concept. Likewise, Pigouvian taxes are corrective taxes, which are used in order to diminish the consequences of negative externalities. Alternatively, subsidies stimulate positive externalities. A more recent approach of Pigouvian taxes can be found in Broadway and Tremblay (2008).

In Figure 3, we have analyzed a negative power externality in production. For example, making furniture by cutting down rainforests leads to a negative power externality to the environment and other individuals in general. The marginal social cost is greater than the individual cost of production. In this case, we clearly see that the society and government are conscientious about the risks and losses ahead, but because the power relations interact jointly with political and economic interests, the best choices in terms of sustainable development policies are not fulfilled. In this case, a fast way to overcome this situation is to exercise institutional power by means of applying public and tax policies through a domestic governance channel that harms the private political and economic interests that cause this injury to the environment.

We see a case of positive power externality in consumption (Figure 4). If you or your city makes use of clean energy, everyone can benefit from this consumption, including the environment. The marginal social benefit from consuming clean energy is greater than individual benefit. Therefore, making use of correct public policies and the mechanisms of governance together with social power relations is a better way for the society to reach a sustainable development agenda.

We may use traditional economic theory’s principles in an interdisciplinary manner. Though economic theory provides important elements for understanding the allocative principles of the market, it is necessary to go beyond these principles. The analysis of economic efficiency and welfare theory gave us just few insights into the importance of considering that there is another entity external to this mechanism, which is also affected by human economic activities, besides the economic agents directly related to the market. This perspective shows how narrow the idea of thinking is, that the market logic alone would solve the inherent problems of the society.

We can think this through with respect to the environment. It is an entity external to economic activities but directly suffers the effects of them. The principle of economic externalities partially considers the effect of human exchanges over an agent external to this mechanism because it sees only the market logic, without considering the integrality of all elements involved in economic activity. In Figure 5, we can see a more complete perspective of the power externality triangle considering different levels of social power, some governance subjects and the political and economic cycles (business cycles). We suggest that the two ways of overcoming externalities should comprise all aspects of the power externality triangle.

Of course, the traditional Pigouvian taxation solution in economics is not the only way to overcome externalities. Nor is it the only analytical way of dealing with externalities in welfare economics. However, our intention is not to strictly follow the neoclassical economic view. We are making inferences with it and pointing gaps which could be useful to design new elements of a more integrated way of thinking. In this sense, we will consider it just as a starting point in our theoretical proposition.

Additionally, we should consider the possibility that these ways of overcoming power externalities do not work at all, since governments may not have enough money or a provisional budget to deal with subsidies in order to improve a positive power externality. On the other hand, governments cannot apply appropriate tax policies in order to correct negative power externalities. Still, there is a chance that groups of interest may interfere in the process of public policies in power externalities due to conflicts about interests and priorities.

With this in mind, let us reflect on the power externality triangle we are proposing. It shows us that beyond the business cycles concept (which encompasses the economic and political cycles), there are two more concepts embracing the governance and social power subjects. These three concepts put together demonstrate that climate change challenges need critical thought and effective action on the part of civil society, business actors, institutions and governments. Despite this, nations’ climate change policies, in terms of effective public polices and societal actions, are not being made in unconditional ways as they should be, as pointed out by Repetto (2008), Biesbroek et al (2010), Keskitalo (2010), Berrang-Ford et al (2011), Ford & Berrang Ford (2011), Wolf (2011) and Jens (2017).

In this sense, we propose a way of thinking about the environmental and climatic issue beyond economics. Our intention is to provide future insights that consider interdisciplinary correlations. This may be an alternative analytical path in terms of propositions for a new economic theory in order to broaden the understanding of the complex phenomena regarding economic intervention and social power relations in climate change governance. In this sense, the next section is a preliminary empirical proposition of a more integrated analysis of the climate change problem considering the interdisciplinary mechanism with social power relations, economics and governance approaches.

3. Evidences of Recent Negative Power Externalities in the Brazilian Climate Change Agenda

Brazil has a legacy of relevant institutional contributions in climate conferences. Brazilian negotiators actively participated in the creation of consensus for the elaboration of the Paris Agreement. Another Brazilian contribution was the suggestion of the design of an instrument that later came to be the reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, globally incorporated within the scope of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Nevertheless, at the national level, recent economic and political instabilities reveal limits and inefficiencies in Brazilian governance with negative implications for the implementation of its climate policy. After a good performance of reductions in deforestation in 2012 and emissions of greenhouse gases, the environmental agenda since 2015 showed setbacks regarding protection of forests and the ways of life of indigenous people and traditional communities. Recent data on the increasing greenhouse gas emissions of key economic sectors, released by the greenhouse gas emission estimate system, showed risks in the achievement of climate policy objectives and goals established before.

This means that, although the Brazilian government has ratified the Paris Agreement, a significant step by Latin America’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, effective and definitive climate actions remain a challenge that is subject to political-economic business cycles. According to United Nations data, Brazil currently emits approximately 2.5 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide and other polluting gases. This is in contrast with its performance last decade where Brazil achieved significant emissions cuts, thanks to its efforts to reduce deforestation in the rain forests and increase the use of renewable sources of energy including hydropower, wind, solar and biomass.

We should remember that countries set their own targets for reducing emissions. The targets are not legally binding, but nations must update them every five years. Using the 2005 levels as the baseline, Brazil has committed to cutting emissions 37 percent by 2025 and there is an intended reduction of 43 percent by 2030. However, after almost three years of a deep economic recession and political crisis, this aim may not be achieved.

The country is faced with the challenge of recovering economic growth and to remodel the domestic political governance structure that suffers from instabilities and corruption. Although the country had committed before to follow a way of recovering economic growth jointly with sustainable development policies with a focus on the aspects of climate change and reduction of greenhouse gases emissions, the current government is embracing the opposite way, such as the cut in the budget of the Ministry of the Environment and amnesty to invaders of public lands.

Another action that demonstrates the current regression in environmental policies was the government’s bet on fossil fuels. The 2026 10-year Energy Plan projects that 70.5 percent of the investments in the energy matrix over the next ten years will go to oil, especially in the exploration of pre-salt reserves. We see a profound contradiction in the environmental policies previously envisaged in the 10-year Energy Plan, since it was originally formulated as a climate change mitigation plan. This is contrary to the country’s own strategic interests. Brazil has several energy solutions in terms of clean technologies such as biomass and biofuels. In addition, the current Temer Government will approve provisional measure number 795, thereby establishing tax exemptions for oil companies.

In this sense, at the national level, the Brazilian environmental policy is going backwards. Additionally, the economic and political crisis in the last three years has influenced negatively the short run government policies since the country faced huge budget constraints, and the most common way of recovering the economy is to appeal to the traditional matrices of production like the oil chain and fossil fuels. Nowadays, there is a lack of effective management and surveillance in the environmental policies that were previously established. This problem became worse when the government announced a cut of fifty percent in the provisions for inspection and environmental surveillance in the 2018 budget of the Ministry of Environment.

“The Paris Agreement has the ability to convert and channel environmental goals into actions through consensual resolutions.”

We should note that the Brazilian society has been living in a climate change governance puzzle for the last three years. The economic crisis, the political instabilities and different sources of social power are interacting in a way that damages the previous environmental commitments. The main power relations that govern this situation are the international institutionalized power and the Brazilian government power. At an international level, we have the institutionalized power relations built in the United Nations and performed through the Paris Agreement and the recent COP 23, held in Bonn, Germany. The required course of action is to inspire the Brazilian government to review and rethink its efforts in promoting actions and measures for mitigation of greenhouse emissions. As mentioned earlier, institutional power gives us the second best solution and denotes the exercise of power through the authority of formal social systems and institutions.

A way to endorse this is through the bottom-up and top-down governance structures, as discussed before. As an international treaty under the United Nations’ protocols, the Paris Agreement has the ability to convert and channel environmental goals into actions through consensual resolutions. The Brazilian government exercises power through the authority of formal institutional systems. In the past, the country had a legacy of important contributions in terms of political proposals and technical body. Now it has declined its performance in terms of leadership in reducing greenhouse emissions and coordination of effective environmental efforts.

“The economic view of free market system is not sufficient to handle the environmental concerns and sustainable development policies.”

We must not forget that together with institutional power there are other potential and informal sources of social power like civil society organizations and groups of environmentalists acting in many ways, inside and outside the country. These are important means for disseminating environmental thinking in order to influence and mobilize effective efforts towards sustainable development policies. Furthermore, these social groups of environmental interest help to combat the political and economic individualist way of thinking that neglects nature and gives it the least priority. With this in mind, we could schematize the negative power externality situation Brazil is facing (Figure 6).

Figure 6 shows us some examples of domestic actions among the three pillars of the power externality triangle. The negative power externality is a combination of diverse elements, which results in injuries to the environment and delays in the accomplishment of climate commitments. Additionally, as we can see on the governance side, there is an absence of strong governance structures and sustainable public policies to overcome the negative power externality in Brazil. In this sense, when contradictory environmental governance actions in the public sector are put together with circumstances of economic crisis and political instability, the effects on climate change policies are quite conflicting, since the fastest way to achieve economic recovery consists in making use of traditional sources of production and energy together. This situation leads to a failure to fulfill the environmental commitments made before.

4. Concluding Remarks

Brazil is facing a climate change governance puzzle in which we can identify economic and political instabilities interacting in a conflicting manner with power relations. The exercise of institutionalized power through the national government and international institutions should be enough to reach an environmental second best outcome—the institutional power coordination of the environmental arrangements. However, the domestic governance and institutionalized power relations are working in a contradictory manner, since the second best solution is not enough to reach an effective agenda for climate change and sustainable development. This is a signal that the economic view of free market system is not sufficient to handle the environmental concerns and sustainable development policies.

In the same context, the free market system generates externalities over the third parties. The environment is seriously damaged due to economic activities as an entity and should not be treated as an object subjected to economic exploitation. Therefore, we should perceive that the efficiency criterion behind the neoclassical postulates is full of gaps. Additionally, we have political instabilities and economic crisis when the institutionalized power relations are working in a conflicting manner. In this sense, we are proposing a more integrated system of analysis through an analytical framework for formulation of public policies and decision-making.

The concept of power externality comprises this proposition. It aims to consider social power relations as the main vertex of the governance puzzle triangle that contemplates the economic market system (with its inherent contradictions) and governance aspects. The negative power externality Brazil faces is a result of the interconnected relations of these three spheres of analytical thought. In the recent Brazilian case, they are influencing the environmental agenda negatively. The Brazilian case we have explored is just a brief example of a future empirical research agenda that may explore this concept and its multidisciplinary interconnections.

The notion of power externality reflects the effects of the power relations and the political-economic activities over the society and the ecosystem. Accordingly, in a situation of negative power externality, although the society and the government are conscientious about the risks and losses ahead, because of the interchangeability between power relations jointly with the business cycles, the best choices in terms of climate change policies and sustainable development are not fulfilled as expected.

Although a negative power externality reflects biases in driving public environmental policies, it must not be a permanent situation, since it could oscillate according to the multiple elements of the dynamic power externality triangle. In this sense, whenever a part of the triangle works in a bad sense in terms of the economic and environmental system as a whole, the power relations could work jointly with the public policies and the governance structures in order to reach an integrated reorientation of the power externality triangle.

As a starting point, the concept of power externality must be further developed considering the dynamic interconnections among economics, governance and social power relations. As we seek to make evident throughout this study, the power externality concept throws light on the gaps of a strictly economic view in order to emphasize the need for a more complete way of theoretical thinking which reveals that the market logic alone cannot be considered when we consider environmental concerns. Actually, it encompasses many agents (or actors) and must contemplate the intrinsic relationship among society, governance structures, environment, politics, economics and social power relations. Further research plans could also be considered to develop a more detailed theoretical system about the nature of power relations in economics and global governance.

Bibliography

- Ritel, H. W. J. and M. M. Weber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4, (1973): 155-169.

- Lazarus, R. J., “Super Wicked Problems and Climate Change: Restraining the Present to Liberate the Future,” Cornell Law Review 94, (2008): 1153-1233.

- Davoudi, S., J. Crawford and A. Mehmood, Planning for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation for Spatial Planners, (London/UK: Earthscan/James and James, 2009).

- Jordan A., D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, T. Rayner and F. Berkhout, eds., Climate Change Policy in the European Union: Confronting the Dilemmas of Mitigation and Adaptation? (Cambridge/UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Martinus J. Vink, Art Dewulf and Catrien Termeer. “The Role of Knowledge and Power in Climate Change Adaptation Governance: A Systematic Literature Review,” Ecology and Society 18, no. 4, (2013): 46.

- Vilfredo Pareto, Manual of Political Economy (London: Macmillan, 1906).

- Elvin Lancaster and Richard G. Lipsey, “The General Theory of Second Best,” The Review of Economic Studies 24, no. 1 (1956): 11-32.

- Garry Jacobs, “Foundations of Economic Theory: Markets, Money, Social Power and Human Welfare,” Cadmus 2, Issue 6, May (2016): 20-42.

- Winston P. Nagan, “The Concept, Basis and Implications of Human-Centered Development,” Cadmus 3, no. 1, oct (2016): 27-35.

- Steven A. Y. Lin and David K. Whitcomb, “Externality Taxes and Subsidies” in Theory and Measurement of Economic Externalities, Steven A. Y. Lin (New York: Academic Press, 1976).

- Nathalie Berta, “On the Definition of Externality as a Missing Market,” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 24, no. 2 (2017).

- Arthur C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare, 4th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1932).

- Robin Broadway and Jean-François Tremblay, “Pigouvian Taxation in a Ramsey World,” Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting Economics 15, no. 2 (2008).

- Repetto, R. “The Climate Crisis and the Adaptation Myth,” Working Paper n. 13, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, (2008).

- Biesbroek, G. R., et al., “Europe Adapts to Climate Change: Comparing National Adaptation Strategies,” Global Environmental Change 20, (2010): 440-450.

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., Developing Adaptation Policy and Practice in Europe: Multi-level Governance of Climate Change (New York: Springer, 2010).

- Berrang-Ford, L., J. D. Ford and J. Paterson, “Are We Adapting to Climate Change?,” Global Environmental Change 21, (2011): 25-33.

- Ford, J. D. and L. Berrang-Ford, eds., Climate Change Adaptation in Developed Nations: From Theory to Practice. Advances in Global Change Research 42. (New York: Springer Science+Business, 2011).

- Wolf, J., Climate Change Adaptation as Social Process, in Climate Change Adaptation in Developed Nations: From Theory to Practice, J. D. Ford and L. Berrang-Ford, eds., (New York: Springer, 2011).

- Marquardt Jens, “Conceptualizing Power in Multi-level Climate Governance,” Journal of Cleaner Production 154, (2017): 167-175.