Hello Visitor! Log In

The Future of Water: Strategies to Meet the Challenge

ARTICLE | October 21, 2013 | BY Alexander Likhotal

Author(s)

Alexander Likhotal

Abstract

Despite the UN’s adoption of a new economic and social right in 2010 - the Right to safe drinking water and sanitation - the deficit of fresh water is becoming increasingly severe and large-scale.

The mounting water crisis and its geography make it clear that without resolute counteraction, many societies’ adaptive capacities within the coming decades will be overstretched.

The scale and the global nature of the water crisis demand a new level of statesmanship, of vision and of international action. To master successfully the threats of water crisis, not only its effects, but essentially its underlying causes must be addressed by implementing structural changes in our water policies and economies. This requires a coherent strategy in which the economic, social, water and environmental aspects of policy must be properly coordinated.

The world needs a standalone comprehensive “water goal” in the post-2015 development agenda, based on principles of equity, solidarity, recognition of the limits of our planet and rights approach, and linking development and environment in analyses and in governance policies. Such a goal would address the three interdependent dimensions of water: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, Water Resources Management and Wastewater Management and Water Quality.

Scientific understanding of water risks and worldwide evidence clearly define the challenges to be addressed and provide a sound basis for policy; the resources required could be made available if the water agenda is given sufficient priority; and the benefits and opportunities of early action are undeniable. In fact, the moral, scientific and practical imperatives for action are established.

The United Nations’ General Assembly recognized a new economic and social right in 2010 - the Right to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Despite the UN’s adoption of this vital principle, the deficit of fresh water is becoming increasingly severe and large-scale – whereas, unlike other resources, there is no substitute for water.

| “The UN Habitat warns that by 2030 more than half the population of huge urban centers will be slum dwellers with no access to safe water or sanitation.” |

While the drinking water target has officially been met according to the UN’s criteria (based on the number of pipelines) and statistics, in reality the existence of a pipe does not necessarily mean there is clean water reliably flowing out of it; and even if there is, it may be very far away, or priced at a rate which some people cannot afford. More worrying still, recent reports show that drinking water availability in Africa is declining, and the UN Habitat warns that by 2030 more than half the population of huge urban centers will be slum dwellers with no access to safe water or sanitation.

The mounting water crisis and its geography make it clear that without resolute counteraction, many societies’ adaptive capacities will be overstretched within the coming decades. This could result in massive migration, destabilization and violence, jeopardizing national and international security to a new degree. As John F. Kennedy rightly observed in the early 1960s: “Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel Prizes - one for peace and one for science.” The observation made 50 years ago has become more appropriate today.

The figures are staggering. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that by 2025 1.8 billion people will be living in regions stricken with absolute water scarcity, while two-thirds of the world population could be living under stress conditions. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) assesses that, by 2025, water withdrawals will increase by 50 percent in developing countries, and 18 percent in developed countries. According to UNEP and UN Habitat, about 80 percent of wastewater from human settlements and industrial sources is discharged to the environment without treatment. Last but not the least, the IPCC report suggests that by 2050 annual average runoff will have increased by 10%-40% at high latitudes and decreased by 10%-30% over some dry regions at mid-latitudes and semi-arid regions at low latitudes.

As always, the cost of no action will be much higher than that of action. The return on investment for providing basic services need not be demonstrated anymore. For safe drinking water and sanitation, the World Heath Organization estimated returns of $3-$34 for each $1 invested depending on the region and technology. Worldwide, more than 7,000 major disasters have been recorded since 1970, causing at least $2 trillion in damage and killing at least 2.5 million people. The Stern Review on Climate Change published in 2006 concluded that by 2050 extreme weather could reduce global GDP by 1% and that climate change could cost the world at least 5% in GDP each year if left unabated. If even more dramatic predictions come to pass, the cost could rise to more than 20% of GDP.

1. Where We Stand Today

There will be 220,000 people at the dinner table tonight who were not there last night—many of them hungry, thirsty and desperate. Population growth is one of the major drivers of the multiple changes taking place around the world, including in terms of economic activity and availability of natural resources like water.

Humanity currently uses half of the accessible 12,400 km3 of freshwater per year. The bad news is that the water use is growing even faster than the population: water consumption in the 20th century grew twice as fast as the world population. As a result, a third of the world’s population lives in water-stressed countries now. By 2025, this is expected to rise to two-thirds.

| “Since 70 percent of world water use is for agriculture, water shortages inevitably translate into food shortages. By 2050, after we add another 3 billion to the population, we will need an 80 percent increase in water supplies just to feed ourselves.” |

The problem of overcoming the water crisis comprises many complex and controversial questions. But thinking about ways of countering the global water crisis, we must first of all recognize its direct causes.

They include:

1.1 The growth of the world’s population and of agricultural, industrial and energy production, which are the main consumers of water;

The global population tripled in the 20th century but water consumption went up sevenfold. Half the world’s people already live in countries where water tables are falling as aquifers are being depleted. Since 70 percent of world water use is for agriculture, water shortages inevitably translate into food shortages. By 2050, after we add another 3 billion to the population, we will need an 80 percent increase in water supplies just to feed ourselves.

Already, around one billion people are chronically hungry, and by 2050 agriculture will have to cope with these threats while feeding a growing population with changing dietary demands. This will require doubling food production, especially if we are to build up reserves for climatic extremes.

To do this requires sustainable intensification - getting more from less - on a durable basis.

1.2 The environmental consequences of economic activities and the destruction of natural ecosystems;

Current estimates of global GDP are around US$ 60 trillion and even at modest per capita growth rates in the emerging economies of the world we could easily see a world (as we conventionally measure it today) with a GDP closer to US$ 200 trillion that would meet poverty targets - three worlds sitting on our present one world but stretched to the limits with regard to consumption and production patterns.

| “The amount of wastewater produced annually is about six times more than the water present in all the rivers of the world.” |

We are polluting our lakes, rivers and streams to death. Every day, 2 million tons of sewage, industrial and agricultural waste are discharged into the world’s water, the equivalent of the weight of the entire human population of 6.8 billion people. 80% of the world’s rivers are now in peril, affecting 5 billion people on the planet. We are also mining our groundwater far faster than nature can replenish it, sucking it up to grow water-guzzling, chemical-fed crops in deserts or to water thirsty cities that dump an astounding 750 million m3 of land-based water as waste in the oceans every year. The global mining industry sucks up another 750 m3, which it leaves behind as poison. Fully one third of global water withdrawals are now used to produce biofuels - enough water to feed the world. A recent global survey of groundwater found that the rate of depletion more than doubled in the last half century.

1.3 Wasteful use of water and other natural resources in an economy driven by hyper profits and excessive consumption;

The amount of wastewater produced annually is about six times more than the water present in all the rivers of the world.

In many places of the world, a staggering 30 to 40 percent of water or more goes unaccounted for due to water leakages in pipes and canals and illegal tapping.

In the US some of the 852 billion litres wasted each year through over-watering can be saved by installing smart systems which deliver just the right amount of moisture.

City landscaping or “urban irrigation” makes up 58 percent of urban water use, besides the water wasted which generates over 544,000 tons of greenhouse gases annually.

U.S. water-related energy use is at least 521 million megawatt hours a year - equivalent to 13 percent of the nation’s electricity consumption.

The carbon associated with moving, treating and heating water in the U.S. is at least 290 million tons a year.

1.4 Mass poverty and backwardness in countries where authorities are not able, and often have no desire to organize effective water management;

Almost two in three people lacking access to safe drinking water survive on less than 2 dollars a day and one in three on less than 1 dollar a day.

World Bank estimates that 53 million more people were trapped in poverty last year, subsisting on less than $1.25 a day, because of the crisis. This comes after the soaring food and fuel prices of recent years, which pushed 130 to 155 million people into extreme poverty, many of whom have still not recovered.

Dirty water is the biggest killer of children; every day more children die of waterborne disease than HIV/AIDS, malaria and war together. In the global South, dirty water kills a child every three and a half seconds. And it is getting worse. By 2030, global demand for water will exceed supply by 40%—an astounding figure foretelling terrible suffering.

It is not surprising that virtually all of the top 20 countries considered to be “failing states” are depleting exponentially their natural assets—forests, grasslands, soils, and aquifers—locked in a vicious circle to sustain their rapidly growing populations.

1.5 The arms race and the senseless waste of enormous amounts of wealth and resources in wars and conflicts;

Roughly ten years ago, James Wolfensohn said he was not able to comprehend why the world spends only 50 billion dollars on development aid annually while it squanders a whopping 950 billion dollars on its armed forces. “If the world’s rich nations spend the 950 billion dollars to really fight poverty and disease,” he argues, “they would not need to spend even 50 billion dollars fighting wars.”

| “US$105 billion was spent on nuclear weapons in 2011, up from US$91 billion in 2010. Shifting spending (and this is mere 7% of the world military budget!) away from weapons to sustainable development would have profound impacts on the lives of over 3 billion people and would promote security and stability around the world.” |

Today, the world spends twice as much on war. Two decades since the end of the Cold War, over 20,000 nuclear weapons still exist, with many on high alert and each weapon much deadlier than those that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. US$105 billion was spent on nuclear weapons in 2011, up from US$91 billion in 2010. Shifting spending (and this is a mere 7% of the world military budget!) away from weapons to sustainable development would have profound impacts on the lives of over 3 billion people and would promote security and stability around the world. Spending US$105 billion annually over five years towards sustainable development could:

- Lift 1 billion people out of poverty.

- Allow 60 million more children to live past their 5th birthday.

- Supply 700 million people with clean drinking water.

- Give 1.3 billion people access to basic sanitation.

- Provide 280 million children with proper nutrition.

In light of these various negative impacts, a question must be posed to political and economic leaders: For them to respond to the water and related environmental crises, and ensure the better management of these resources, how severe must the resource and ecological risks on a nation’s economy become before they act, and how do these factors affect a nation’s ability to pay its debts?

There are many economic justifications for action. A 10% drop in the productive capacity of soils and freshwater areas alone could lead to a reduction in trade balance equivalent of more than 4% of GDP.

And we should start thinking not exclusively in terms of associated expenses, but also in terms of the cost of not providing access to water. People without access to basic water supplies and sanitation, especially in Asia, Africa and Latin America, work fewer days because of illnesses and diseases. WHO estimates that meeting the MDG goal for water and sanitation by 2015 will result in productivity gains above US$700 million per year solely from there being fewer cases of diarrhea for health systems to manage.

2. The Water-Energy Nexus

The water crisis cannot be decoupled from its energy dimension.

Europe’s power sector accounts for 44% of all water withdrawals, and 8% of consumption – mainly evaporation in cooling towers. China already faces a water shortage of 40 billion m3 per year, yet coal-fired generation is expected to increase 43% by 2020. It already accounts for around 60% of total industrial water demand. Peter Evans, Director for global strategy and planning at General Electric Co., told during a Tokyo conference that Asian utilities are “assuming the water is there. They actually will not be able to build as many coal plants as the projections suggest.”

Coal, gas and nuclear power generation all use large amounts of water. Of these, nuclear is the thirstiest. A combined-cycle gas turbine plant of around 450 megawatts could consume 74 million m3 of water during its lifetime, and a coal-fired power station of 1.3 gigawatts no less than 1.4 billion m3. The latter figure is seven times the annual water consumption of Paris.

By contrast, wind and PV generation use very little water. The renewable technologies that consume water are solar thermal electricity generation, biomass and waste-to-energy, geothermal, and in a more direct sense, hydro-electric.

Policy-makers are showing signs that they are increasingly prepared to ensure the energy sector pays an appropriate cost for the water it uses. The European Union has reviewed its water policy goals as part of its Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Waters.

But in the US, the energy sector’s use of water looks like it is set to soar despite the deployment of renewable energy. This is because of non-conventional gas. While shale gas has become a live political issue in that country, coverage has almost purely focused on the issues of fugitive emissions, ground-water contamination, and whether the process should be regulated at a Federal or State level.

What has not been debated is the actual consumption of water.

Chesapeake Energy Corp. reports that drilling a deep shale gas well requires up to 2,000 cubic metres of water, but the “fracking” process requires, on average, an additional 20,000 cubic meters to be injected per well at high pressure to break up the rock. Multiply this by the hundreds of thousands of fracked wells needed to meet the increasing gas demand in the coming decades, and that’s a lot of water. Some may be reusable, as long as the salinity is not too high, while some may require a significant amount of wastewater treatment and energy. The costs of this post-processing must be accounted in the price of shale gas energy.

Fracking supporters like to compare its water use with that of corn ethanol – not exactly a champion for the rational, fact-driven deployment of clean energy. The real comparison should be between gas-fired generation based on fracking, and wind or PV. On that count, the water factor comes down strongly in favour of renewable energy.

| “To meet the threats of water crisis successfully, we must address not only its effects but also essentially its underlying causes, by implementing structural changes in our water policies and economies. This requires a coherent strategy in which the economic, social, water and environmental aspects of policy must be properly coordinated.” |

3. What Next?

The scale and the global nature of the water crisis demand a new level of statesmanship, of vision and of international action. To meet the threats of water crisis successfully, we must address not only its effects but also essentially its underlying causes, by implementing structural changes in our water policies and economies. This requires a coherent strategy in which the economic, social, water and environmental aspects of policy must be properly coordinated.

Major issues, whose scale and importance were not reflected in the MDGs, are those of our decreasing per capita water supplies, of the overuse and sometimes irremediable pollution of our watersheds, of the predicted conflicts over water usage and of the looming impact of climate change on the water cycle. The process that led to the adoption of the MDGs had only retained the humanitarian aspect of these well-established trends.

Today the world needs a standalone comprehensive “water goal” in the post-2015 development agenda linking development and environment in analyses and governance policies. Such a goal would address the three interdependent dimensions of water: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, Water Resources and Wastewater Management and Water Quality. Setting the goal will not be an instant “silver bullet” solution. But it would reflect the needed awareness and mobilization of those who have the power to make things change.

The goal must be based on principles of equity, solidarity, recognition of the limits of planet and rights approach, coupled with effective means to check and demand the accountability of all stakeholders. It should help distinguish between the different aspects of water use and the related rights and obligations of different participants in this process at the local, national and international levels.

It should advance water innovation, smart water solutions and recycling that need to be introduced in the next 5-10 years.

Water justice must become a recognized and operational element of new water strategy. The UN’s resolution declaring water as a human right urges States and international organizations to provide finance, capacity-building, and technology transfer through international assistance and cooperation, especially to developing countries.

In rich countries, the state has invested in water infrastructure over the centuries and progressively asked consumers to cover the cost of water services. Many developing countries are so deeply in debt that the state is unable to invest in infrastructure without the support of the international community. We cannot expect poor people to pay for water infrastructure; most people could possibly pay a reasonable, affordable charge for their water services.

Therefore, the new financial mechanisms urgently need to be put in place. Decentralised financing and cooperation must be enhanced, including targeted development loans guaranteed by local authorities from the North.

In conclusion, a scientific understanding of water risks and worldwide evidence clearly define the challenges to be addressed and provide a sound basis for policy; the necessary lines of action have been identified; the resources required could be made available if the water agenda is given sufficient priority; and the benefits and opportunities of early action have been demonstrated. In fact, the moral, scientific and practical imperatives for action are established.

ADDENDUM

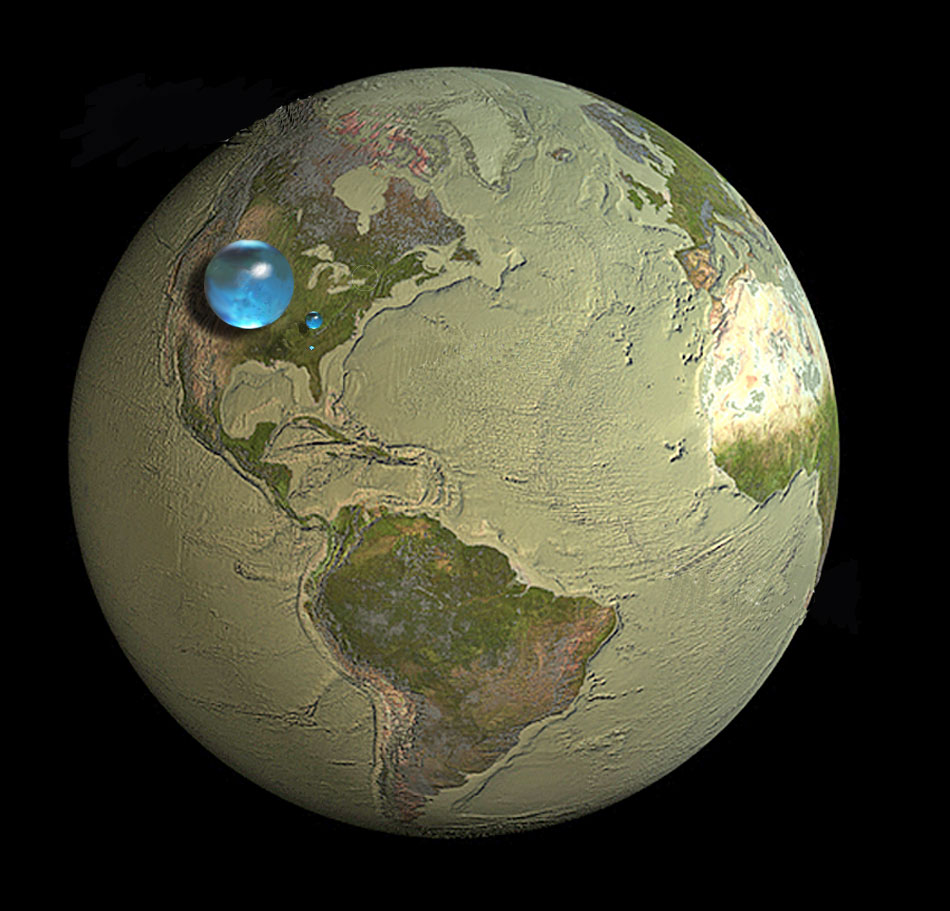

The Actual Volume of Water on Earth*

We are used to think of the Earth as “blue planet”, more than two-thirds of the surface of which is water. But the world‘s oceans is a very thin layer of water when you compare it to the scale of the planet. Experts of the U.S. Geological Survey created the infographic that demonstrate how small – in comparison with the Earth – the volume of water we have.

The biggest blue sphere – it is all the water on our planet, including the one that is inside the bodies of plants and animals and people. The diameter of the sphere is 1,384 kilometers, and its volume is 1.386 billion cubic kilometers. Scope of smaller volume – a liquid fresh water in all the rivers, lakes, wetlands and groundwater. Its volume – 10,633,450 cubic kilometers.

Finally, a tiny blue dot – this is fresh water of all the lakes and rivers on the planet, which amounts to 93,113 cubic kilometres.

* Department of the Interior/USGS, U.S. Geological Survey/photo by Jane Doe

- Login to post comments