Hello Visitor! Log In

Backwardness, Growth & Distribution: Institutional Structure of Capitalism

ARTICLE | June 25, 2021 | BY Joanilio Rodolpho Teixeira

Author(s)

Joanilio Rodolpho Teixeira

Post-Keynesian and post-Kaleckian approaches, as part of the heterodox family, have been progressing fast in the last few decades. They have made important contributions to the socio-economic thought, providing necessary opportunities to alternative policies as well as significant stimulus for new areas of research. They are not immune to controversies and probably a combination of the two alternative schools will illuminate future projects and actions to get a better society for the majority of the world population. Kaldor (1971, p. XXIX) mentions: “I have never felt that one’s understanding of economic process has reached a stage where it is no longer liable to radical revision development in the light of new experience”.

The above perspectives suggest a number of socio-economic and institutional reforms to make the society sounder and fairer. No doubt, serious policy proposals need to be examined in order to tackle some unacceptable social effects of poverty, instability and distribution of wealth and income. However, the fundamental dilemma is how to implement fair actions. This is a hard task due to the fact that the core of economic policy, in most countries, is to a large extent directed by those that already have and would like to preserve their privileges, as pointed out by Kalecki (1943, p. 138): “The assumption that a government will maintain full employment in a capitalist economy if only it knows how to do it is fallacious.” Because it weakens their power over workers. Up-to-date views are required. We have seen the challenges brought by the forces of “populism” over governance. It is necessary to rethink the meaning of backwardness/ development/ gender/ racial/ ethnic/ democracy/ democratizing.

We point out that some post-Keynesian and post-Kaleckian proposals condemned by the majority of the orthodoxy to mockery, mostly at the end of the last century, are getting increasing media success and academic respect. For instance, in the last colloquium organized by WAAS, we find spacious discussions of heterodox economic ideas concerning fiscal policy and other themes. Participants in those events expressed the feeling that the rich tend to dominate the capitalist society illegitimately, paving the way to unfair social inequality. Researchers are frequently expressing themselves in support of increasing level of taxation on fortunes and successions. Indeed, the themes of uncertainty, power, institutions, crisis and their implications deserve profound attention. For instance, the world is facing the coronavirus crisis today. Latin-America’s outbreak is worse than ever. This negative moment has severe human and social costs, requiring a profound understanding of the nature and causes of our real needs.

Scholars and politicians are much more open nowadays to structural change than before the recession which took place at the beginning of this century. However, a number of fundamental questions do not seem to have been properly asked. For instance, those concerned with political power (mark-up) which in the capitalist society resides mainly with multi-national enterprises that are beyond the control of governments. They, frequently, may even undermine government and put whole communities out of work by speculation and switching capital elsewhere. Also, they tend to buy the media so that few alternative opinions can be clearly expressed, breaking sanctions, destroying the national environment and advertising “fake news”. In many countries, votes of private citizens have less and less efficacy when the real power resides not with proper councils or parliaments, but with the boardroom. How can desirable policies be established in such a way that they could bring such enterprises to serve the socio-economic and political interests of the society? These include greater employment and education, evolution of productivity, expansion of growth and income distribution, reduction of risks, improve health and environment. Public Administration is the actor most responsible for avoiding and/or overcoming a crisis.

“We need proposals which not only interpret the world but explain how to pursue an enlightened global civilization. We need a wider vision that will bring fair dividends to people and nature.”

According to Bhaduri (2010, p.24), “(...) the success of development must be judged from the viewpoint of the least advantaged in society.” He also stresses that: “Nothing is more destructive to a political system than the lack of hope for a better future.” We need to be concerned with the present state of affairs. Gramsci (1977) says: “If the sceptic takes part in the debate, it means that he thinks that he can convince people. That is, he is no longer a sceptic.” This is my case. Actually, in the formulation of actual socio-economic policy, it is useful to add a myriad of remedies (multipliers) together, instead of the simple mathematical exercises and orthodox theories. It is necessary to figure out how to expand the rate of growth of the economy, reduce unemployment, improve distribution of income, etc., in an elusive quest to get a country on the path of desirable living standards.

If we consider the possibility to combine parametrical changes in the post-Keynesian and post-Kaleckian models, given the existing economy, it is possible to suggest some interesting points. For instance, in a country in depression, a larger size of governmental expenditure may well promote increasing equity with no adverse effect on growth. This possibility reflects the belief to implement a strategy based on a better functioning government, which tends to lead to target transfer programmes to disadvantaged groups. This strategy is especially required in Latin America in the present pandemic period. New theoretical perspectives and leadership are required in order to stimulate a fair transition to a new paradigm. As WAAS’ motto indicates, “promoting leadership in thought leads to action”. Rigorous implementation of such amalgams remains difficult, but it seems preferable to admit complexities rather than to be inside over-simplifications. For an overview of such economic theory, see Teixeira (2018).

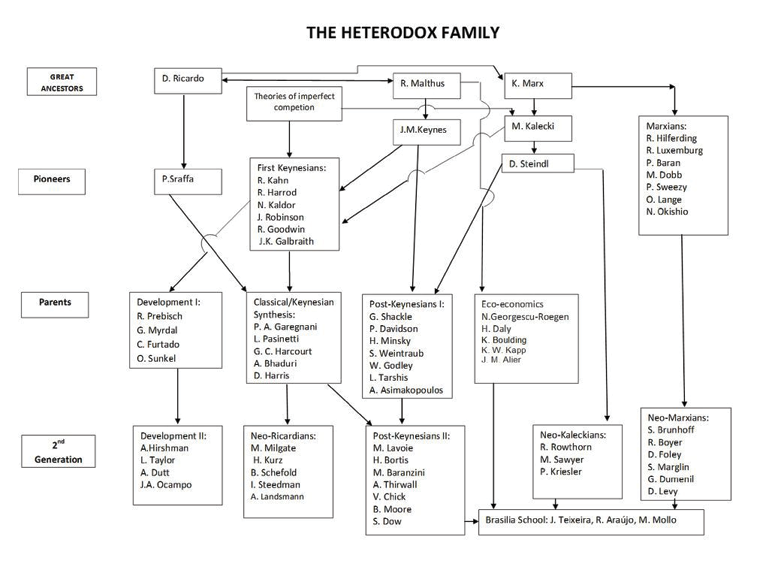

Some contributions and explanations of such complexities have been considered by members of the FAMILY TREE below. Inspired by heterodox visions of post-Keynesian and post-Kaleckian economists, Political Economy has a battle to fight against the status quo. This has been a hard fight which deserves considerable attention. As Brecht (1980) points out, “One of the chief causes of poverty in science is usually imaginary wealth. The aim of science is not to open a door to infinite wisdom, but to set a limit to infinite error. Make your notes.”

As expressed by Jacobs (2016, p. 22), “The only legitimate objective of economic science is a system of knowledge that promotes the welfare and well-being of all humanity”. In this vein, we need proposals which not only interpret the world but explain how to pursue an enlightened global civilization. We need a wider vision that will bring fair dividends to people and nature.

References

- Amit Bhaduri, Essays in the reconstruction of Political Economy, (Delhi: Aakar Books, 2010)

- Bertold Brecht, Life of Galileo, (London: Bloomsbury, 1980)

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from Political Writings, (London: Lawrence and Wishart Ltd., 1977)

- Garry Jacobs, “Foundations of Economic Theory: Markets, Money, Social Power and Human Welfare,”Cadmus 2, no. 6 (2016).

- Nicholas Kaldor, “Conflicts in National Economic Objectives,” The Economic Journal 81 no. 321 (1971)

- Michal Kalecki, “Political Aspects of Full employment,” Political Quarterly 14 no.4 (1943).

- Joanilio Rodolpho Teixeira, “Heterodox Macroeconomic Models of Growth & Distribution,” in Essays on Political Economy and Society Book organized by J. R. Teixeira & D. S. Pinheiro (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2018)